INTRODUCTION

Wearable technology (WT) has become increasingly integral to healthcare, offering real-time monitoring of physical activity, heart rate, sleep quality, and other vital indicators. Devices such as smartwatches and fitness trackers are no longer reserved for elite athletes but are widely used by the general population to track health behaviors and promote lifestyle changes.1,2 The growing popularity of these technologies is attributed to their convenience, affordability, and ability to support preventative care, chronic disease management, and improved patient engagement.3,4 In higher education settings, wearables also hold promise for supporting student well-being by promoting physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior.5 However, as their use becomes more prevalent, critical questions emerge about who benefits from these tools and under what conditions they are effectively adopted and used.

WT includes a wide range of consumer devices, such as smartwatches, fitness trackers, pendants, and other sensor-enabled tools that monitor physical activity, cardiovascular function, and sleep behavior.1 These devices vary considerably in cost, with entry-level models available for under $50 and premium smartwatches exceeding $400, often limiting access for socioeconomically disadvantaged groups.1,3 Although marketed broadly as tools for self-monitoring and wellness, WT holds particular promise in reducing health inequities, given the disproportionate burden of cardiovascular disease among African Americans.6 By enabling real-time monitoring of vital signs and encouraging health-promoting behaviors, WT could serve as an accessible strategy to help mitigate disparities in cardiovascular outcomes if issues of affordability and cultural relevance are addressed.1,2,4 Evidence increasingly highlights the potential of WT to improve cardiovascular health outcomes by promoting early risk detection, physical activity, and adherence to preventive care recommendations. Dhingra et al.5 found that individuals with or at risk for cardiovascular disease who adopted WT were more likely to engage in health monitoring behaviors, highlighting WT’s role in secondary prevention. Similarly, research shows that WT can provide continuous physiologic data, including heart rate variability and arrhythmia detection, which may enhance clinical decision-making.1 These benefits extend beyond individual monitoring; indeed, WT offer scalable methods for fitness assessment and cardiovascular risk reduction across diverse populations.2 These findings suggest that WT not only supports self-management but also contributes to broader public health strategies aimed at reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Beyond clinical applications, WT adoption intersects with critical issues of health equity and social justice. The expansion of wearable health tools is reshaping healthcare delivery, yet access remains stratified along socioeconomic lines.3 Without intentional strategies to improve affordability and usability, WT risk reinforcing the digital divide rather than alleviating it.4 This concern is particularly relevant for African American communities, who face elevated risks for chronic disease while also encountering systemic barriers to technology adoption.5 Integrating an equity lens into WT deployment means addressing affordability, cultural relevance, and digital literacy.6 Ensuring that vulnerable populations benefit equitably from these technologies requires policies and practices that bridge gaps in access and design, aligning WT adoption with broader goals of health justice.

Evidence indicates that racial and socioeconomic disparities influence technology access, including wearable devices. African American populations experience a higher burden of chronic health conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, which WT could help address through early detection and behavior tracking.7 However, research suggests that adoption and sustained use among African American users may be limited by factors such as affordability, perceived usefulness, digital literacy, and cultural fit.8,9 Among university students, these disparities can be further compounded by age, employment status, and academic standing, influencing students’ health behaviors and willingness to engage with wearable devices.6,10 These gaps highlight the need to investigate how wearable health technologies are used within underserved student populations and what barriers may prevent equitable engagement. To address these issues, this study explores the adoption, usage patterns, and perceived barriers to wearable technology among African American university students. By analyzing self-reported data on usage behavior and non-use justifications, this study aims to identify trends in device engagement and understand how demographic and social factors affect wearable adoption.

METHODOLOGY

This study used a cross-sectional survey design to examine WT adoption, usage patterns, and perceived barriers among African American university students. The aim was to identify behavioral trends and demographic influences on WT use, with a focus on understanding disparities related to age, gender, academic status, and employment. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling using targeted outreach via social media, student organizations, and academic networks. Eligible participants were full-time undergraduate or graduate students who self-identified as African American and were aged 18 years or older. A secure online survey was used for data collection. Before beginning the survey, participants provided informed consent in accordance with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval guidelines from Howard University (2025-1811). Participation was voluntary, responses were anonymous, and the study posed minimal risk. All data were stored securely in compliance with ethical standards.

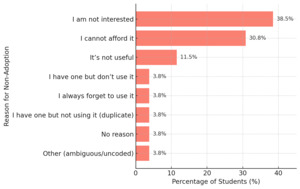

Data was collected using a custom-developed demographic and WT usage questionnaire. This instrument captured participant characteristics (age, gender, student level, and employment status), WT adoption status (user vs. non-user), reasons for use or non-use, and frequency and purpose of WT use. For users, data were collected on primary features used, such as exercise tracking, step counting, and heart rate monitoring, and frequency of use, categorized into low (infrequent), moderate (somewhat regular), and high (regular) usage. Non-users were asked to select reasons for non-adoption from a list that included cost, lack of interest, perceived lack of usefulness, and other write-in options (see Table 1).

Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics to summarize participant demographics, WT adoption status, frequency of use, and reported reasons for use or non-use. Frequencies and percentages were calculated to illustrate usage trends and to compare WT engagement across age groups, gender, academic status, and employment. The analysis focused on identifying observable patterns and disparities in adoption and behavior without conducting inferential statistical testing. All responses were organized and processed using Microsoft Excel to ensure consistency, accuracy, and clarity in presenting the findings.

RESULTS

Table 2 presents descriptive data regarding participant demographics. The final sample included 75 African American university students. Most participants identified as female (n = 59, 78.7%), followed by male (n = 15, 20.0%), with one participant identifying as non-binary (1.3%). Most participants were over the age of 22 (n = 53, 70.7%), while the remaining were between 18 and 21 years old (n = 22, 29.3%). In terms of academic level, 45 students (60.0%) were graduate students, and 30 (40.0%) were undergraduates. Socioeconomic indicators revealed that more than half of participants (54.7%, n = 41) were receiving financial aid. Additionally, 22 participants (29.3%) were employed part-time, and 11 (14.7%) were employed full-time while attending school.

Overall, 65.3% (n = 49) of participants reported using wearable technology (WT), while 34.7% (n = 26) did not. Adoption rates differed across demographic groups. Participants over age 22 had a higher adoption rate (67.9%) than those aged 18–21 (59.1%). Similarly, graduate students were more likely to use WT (68.9%) compared to undergraduates (60.0%). Gender differences were observed as well, with female students adopting WT at a rate of 69.5% compared to 53.3% among male students and 0% among non-binary students. Adoption rates among employed participants were relatively consistent, with 66.7% of unemployed students and 64.3% of employed students reporting WT use (see Table 3).

Among WT adopters (n = 49), usage frequency varied. Over half of users (55.9%) reported using their devices daily, while 29.4% used them several days per week, and 14.7% used them rarely. Participants reported diverse reasons for using wearable devices. The usage purposes included exercise and workout tracking (n = 38), step counting (n = 29), heart rate monitoring (n = 18), calories tracking (n = 9), sleep tracking (n = 5), stress monitoring (n = 1), time tracking (n = 1), notification tracking (n = 1), tasks reminders (n = 1) and other functions such as messaging and weather tracking (n = 4). See Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study provide important insight into WT use among African American university students, revealing both promising engagement and persistent disparities. While over 65% of participants reported using WT, significant variation existed across demographic groups. Older students, graduate students, and females demonstrated higher adoption rates, mirroring previous research showing that age, educational level, and gender are strong predictors of digital health adoption.6,11 Among adopters, primary uses included exercise tracking, step counting, and heart rate monitoring, similar to findings by Passos et al., who noted these functions as common motivators for WT use.2 However, frequent usage was not universal, as many reported only occasional use, indicating that ownership alone does not guarantee consistent engagement. This underlines the importance of not only access but also ongoing motivation and relevance in ensuring WT tools are effectively integrated into students’ health routines. Moreover, this study raises questions about whether adopters experienced tangible benefits from their devices. Although the survey did not directly capture perceptions of improved health outcomes, prior research has linked WT adoption with greater physical activity, enhanced cardiovascular self-monitoring, and improved adherence to health goals.1,5 Participants in this study reported using wearables primarily for exercise and step tracking, suggesting an intention to use these tools for health promotion. Future mixed-methods research should incorporate open-ended questions to explore users lived experiences, including whether they perceive real benefits from adoption, and how such perceptions vary across demographic subgroups.

Barriers among non-users were largely related to lack of interest and cost, consistent with literature identifying affordability and perceived usefulness as major limitations to adoption among marginalized populations.8,12 With over 54% of participants receiving financial aid and nearly half unemployed or only working part-time, the financial demands of WT devices present a real equity issue. Previous studies have shown that lower-income individuals, particularly within African American communities, are less likely to own and consistently use health-related technologies.12 These barriers, if unaddressed, risk widening the digital divide, where health-promoting innovations are disproportionately used by those with more resources. As shown in the research, achieving equitable health outcomes through wearable technology requires targeted strategies to reduce cost-related exclusion and ensure usability across diverse populations.4 At the same time, wearable devices present potential concerns that extend beyond cost and motivation. Some individuals may feel uncomfortable with the surveillance-like nature of constant monitoring, particularly within marginalized groups that already experience heightened scrutiny in daily life.13 Moreover, digital literacy challenges and health literacy limitations may prevent certain individuals, especially those outside university populations, from realizing the full benefits of WT.7,8,14 Addressing these concerns will require culturally sensitive education and careful communication about data use, privacy, and the empowerment potential of self-monitoring technologies.

This study contributes to the growing call for equity-focused design and deployment of digital health interventions. Wearable devices offer real opportunities to address chronic disease risk and promote healthy behaviors, particularly in underserved groups facing elevated health burdens.15,16 However, to realize this potential, institutions must implement strategies that support not only WT access, but also culturally tailored education and behavioral integration. For example, universities could consider lending programs, subsidized devices, or health education modules that directly connect WT to student well-being. As Al-Emran et al. emphasize, inclusive technology initiatives must account for socioeconomic context and the lived experiences of users.17 Without such approaches, wearable health technologies may inadvertently reinforce existing disparities rather than reduce them. This study underscores the importance of ensuring that digital health advancements are accessible, relevant, and empowering for all students, especially those from historically underserved communities.

This study has several limitations. First, the use of a cross-sectional survey design limits the ability to infer causal relationships between demographic factors and wearable technology (WT) adoption or usage patterns. Second, the reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases, including recall bias and social desirability bias, which may affect the accuracy of responses regarding WT use and perceived barriers. Additionally, the sample was recruited through convenience sampling and may not be representative of all African American university students, particularly those attending different types of institutions or from varying geographic regions. The relatively small sample size (n = 75) further limits generalizability and restricts the use of inferential statistical analyses. Lastly, the survey did not explore the specific brands or models of WT devices used, nor did it assess participants’ digital literacy or access to supporting technologies such as smartphones, which could influence WT engagement. Future research should consider longitudinal designs, larger and more diverse samples, and mixed-methods approaches to gain a deeper understanding of WT use and equity in digital health engagement. Moreover, only one participant identified as non-binary, and the study did not capture other LGBTQ+ or multiracial identities. More research should explicitly recruit and analyze these groups to better understand how intersectional factors contribute to patterns of adoption and barriers in wearable health technology. Indeed, wearable devices could serve as tools for queer self-expression, suggesting that adoption among LGBTQ+ individuals may be shaped by identity-related motivations not reflected in conventional survey categories.18 Similarly, medical wearables should be intentionally designed and deployed to advance health equity, underscoring the importance of including racially and socially diverse populations in research to avoid reinforcing inequities.19 Ensuring broader representation in future studies will help clarify how intersecting identities influence both access to and the perceived value of wearable technologies.

CONCLUSION

This study highlights both the promise and the challenges of WT adoption among African American university students. While most students reported using WT, significant disparities in adoption were evident across demographic subgroups, particularly related to age, gender, and socioeconomic status. Key barriers such as affordability and lack of perceived usefulness reveal ongoing equity concerns that must be addressed to prevent widening gaps in digital health engagement. As wearable devices continue to gain popularity for promoting self-monitoring and preventive care, higher education institutions and health technology developers should ensure that access and support are equitably distributed. Efforts to reduce financial barriers, increase digital literacy, and align device functionality with student needs could help bridge the gap. Beyond practical considerations, this study contributes to broader health equity and social justice frameworks by showing how the uneven adoption of wearable devices risks reinforcing systemic inequities in chronic disease outcomes. Prioritizing culturally relevant and inclusive interventions could help ensure that wearables empower rather than exclude historically underserved populations.

Disclosures

By submitting to BCPHR, the authors declare that:

-

They contributed to the creation of the submission and grant BCPHR permission to review and, if selected, publish their work.

-

They do not have personal, commercial, academic, or financial interests that influence the research and opinions represented in the work submitted to BCPHR.

-

The submission is not under consideration by another publication and has not previously been published elsewhere.

_and_wt_usage_purpose_(b).png)

_and_wt_usage_purpose_(b).png)