INTRODUCTION

The legal and political landscape surrounding abortion care access in the United States has undergone dramatic changes in recent years. Before the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the constitutional right to privacy, rooted in the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment, extended to a woman’s right to choose to have an abortion. However, following the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case, which overturned the landmark Roe v. Wade ruling, abortion rights were no longer protected under federal jurisdiction, allowing individual states to determine their laws on abortion.1 Alongside these adjudications, the United States has surpassed other industrialized nations in having the highest maternal mortality rate, with a reported 23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births,2 calling for attention to the factors, such as limited abortion access, influencing maternal health outcomes.3

Legal barriers restricting abortion access have created significant challenges for those in need of care.4 These obstacles not only limit access to essential services, such as abortion and miscarriage care, but also intersect with broader systemic health inequities towards marginalized populations, including the LGBTQ+, Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities. For instance, studies indicate that racially marginalized individuals frequently encounter stigmatization and hostility from healthcare providers, which further limits their access to abortion care.5,6 Moreover, gaps in sexual health curricula contribute to a lack of knowledge about abortion care resources, perpetuating delays and hesitancy in seeking necessary services.4–6 Given these challenges, examining the link between abortion access and maternal mortality in the United States through recognizing the role of intersectional factors like race, socioeconomic status, and gender identity in substantially shaping the diverse experiences of individuals seeking reproductive healthcare highlights the disparities in outcomes across different communities. As a result, the concept of syndemics—where two or more interrelated health issues, exacerbated by social and structural factors, co-occur and interact within a specific population—provides a powerful lens to assess the intersection of abortion access and maternal mortality.7

While several studies have examined the relationship between abortion care access and maternal mortality, all were conducted prior to the 2024 presidential election.8,9 By providing a new and more recent framework for understanding these findings, this research aims to contribute to the ongoing discourse on how restrictive abortion policies directly and indirectly exacerbate abortion-related maternal mortality. Additionally, existing studies have explored the link between limited abortion access and increased maternal mortality, but our causal loop diagram offers a more comprehensive understanding by integrating health policy, stigma, and key interventions like sexual health education, provider training, community advocacy, and improved reporting. By illuminating the dynamic connections between abortion care access and maternal mortality, our research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how restrictive abortion policies contribute to adverse maternal health outcomes. Furthermore, this review seeks to inform policy and advocacy efforts to create equitable, inclusive, and accessible reproductive healthcare systems that address this urgent public health crisis.

METHODS

We conducted a non-systematic review of the literature (NSRL) to examine the linkage between restrictive abortion access and maternal mortality in the United States by focusing on the intersectional factors influencing these outcomes. Due to its flexibility and exploratory nature, we chose the NSRL method, which allowed us to showcase a diverse range of perspectives that may not fit within the constraints of a systematic review framework or encompass the multifaceted nature of abortion and maternal mortality by excluding relevant political, social, and behavioral determinants.

Our review included both qualitative and quantitative studies addressing the impacts of abortion restrictions on maternal mortality rates, legal implications of restricted access to reproductive healthcare, and intersectional factors such as stigma, socioeconomic status, educational background, and minority stress. Preliminary research led us to search key terms to identify potential determinants of restrictive abortion access, including but not limited to “abortion access effect on maternal mortality,” “geographical location and state abortion laws,” “socioeconomic and informational barriers,” “minority stress,” “comprehensive sexual health education,” and “healthcare provider bias.” This strategy guided our search for academic peer-reviewed articles, policy briefs, and relevant grey literature.

We reviewed and synthesized insights from various sources, enabling us to conduct a comprehensive, non-systematic literature review. To ensure an inclusive range of perspectives, not all the studies we included focused solely on limited abortion access and maternal mortality; some addressed broader reproductive health issues within marginalized populations, such as women of color and individuals of low socioeconomic status.

Subsequently, we developed a causal loop diagram (CLD) using Vensim Software to map key determinants and outcomes. CLDs are widely recognized in health systems research for their utility in visualizing complex causal pathways and identifying syndemic factors. The development of the CLD does not necessitate a formal systematic review as non-systematic methods allow for an extensive exploration of multifaceted health issues.

RESULTS

Determinants of Maternal Mortality Among Individuals Seeking Abortion Care

Legal Restrictions on Abortion

A significant determinant linking abortion and maternal mortality is legal restrictions. Our NSRL review strategy explored factors influencing access to abortion services and the interplay between societal stigma around abortion and legal restrictions.

Individuals seeking abortions will often obtain them through licensed healthcare providers or resort to unsafe methods, which untrained individuals frequently perform outside of a proper medical setting.10 Legally performed abortions are typically safe and lead to fewer medical complications. Between 1998 and 2010, the United States reported a mortality rate of 0.7 deaths resulting from legally performed abortion procedures per 100,000 overall fatalities.11 In contrast, unsafe abortions are a leading cause of maternal mortality and morbidity, with complications such as hemorrhage and sepsis arising from substandard clinical practices.10 Globally, maternal mortality rates associated with unsafe abortions range from 4.7% to 13.2% annually—significantly higher than mortality rate for legal procedures.12

Social stigma exacerbates the prevalence of unsafe abortions, limiting access to safe abortion services by fostering restrictive laws and deterring individuals from seeking proper care.13 As the stigma against abortion increases, support often shifts toward public officials who oppose abortion access, leading to the enactment or enforcement of restrictive legislation.14 These laws frequently portray individuals seeking abortion care as irresponsible or selfish and frame abortion itself as inherently harmful or unsafe.15 Societal stigma, often rooted in cultural and religious pressures, not only reinforces restrictive legislation but is also amplified by legal rhetoric surrounding abortion. The cyclical relationship between stigma and restrictive policies perpetuates barriers to accessing safe abortion care and worsens public health outcomes.

Access to legal abortion services offers a dual benefit: it increases the availability of safe procedures while significantly reducing mortality rates from unsafe abortions. These connections highlight the critical role of accessible legal abortion services in mitigating preventable deaths.

Healthcare Provider Bias

Healthcare provider bias can discourage patients from seeking abortions by contributing to the stigma surrounding the topic. For instance, healthcare provider engagement correlates with a decrease in a patient’s socioeconomic status, specifically their neighborhood and household income.16 Many providers also harbor implicit racial and ethnic biases, with preferences for White patients over patients of color.17 Consequently, obstetric racism and biases regarding age, race, and marital status remain as barriers to family planning.10,18

The stigma surrounding abortion operates at multiple levels—individual, community, cultural, institutional, and legal—impacting how providers deliver care.19 Providers may adopt hostile, moralistic, and cold behaviors, which can include questioning or second-guessing individuals considering abortions. Such biases can manifest as a lack of empathy or insensitivity and ultimately discourage individuals from seeking necessary services.19

Additionally, current trends indicate that medical residents studying gynecology and obstetrics avoid practicing in states with abortion bans.20 Consequently, providers who remain in those states may hold more bias against administering abortion care, likely due to personal stigma against abortion, agreement with state policies, or fear of prosecution.21 For women in areas with abortion bans, this creates significant challenges to finding and traveling to abortion facilities in other states. At the same time, the persistent lack of providers limits access to essential gynecological care unrelated to abortion.

Stigma and Patient Distrust in the Healthcare System

Patient distrust can also exacerbate maternal mortality by limiting abortion access. When patients perceive or experience stigma held by healthcare providers, which may manifest as implicit judgments, false beliefs based on patients’ race and socio-economic status, and/or reluctance to provide timely abortion care, they may lose trust in medical professionals and the healthcare system at large.22

As a result of societal stigma and healthcare provider bias, patients often delay seeking care for fear of further negative abortion care experiences. Hesitancy to initiate care means that patients reach greater gestational ages upon linkage to care, limiting abortion options and leading to medical complications. Compared to women who received abortions in the first nine weeks of pregnancy, those doing so later in pregnancy are more likely to die from abortion-related causes, as the mortality rate is less than 0.3 per 100,000 for abortions performed in the first nine weeks of gestation, but increases to 11 per 100,000 for abortions after 21 weeks of gestation.12

With greater gestational ages, patients are also more likely to be denied abortions due to legal restrictions or safety concerns. An important study outlining the effects of abortion access on maternal health, known as the Turnaway Study, demonstrated that being denied an abortion was associated with elevated levels of anxiety, stress, and lower self-esteem immediately following the denial.23 Although mental health outcomes generally improved for these patients within a year, perceived abortion stigma at the time of seeking an abortion was still associated with negative psychological outcomes that remained impactful for multiple years.23 Additionally, patients who were denied abortions were found to have an almost four-fold increase in the odds that their household income would fall below the Federal Poverty Level.23 Women who were denied abortions went on to experience more debt, lower credit scores, and worse financial security for multiple years following the denial.23 These adverse maternal health outcomes and consequences of being denied abortions point towards the impact of patients’ initial distrust and skepticism on their seeking medical care, which can be traumatic for many communities.

Another factor contributing to patient distrust in the healthcare system is the existence of crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs). These facilities are typically affiliated with religious organizations and deceivingly portray themselves as medical professionals. They use different tactics to target vulnerable abortion seekers and persuade them to keep their pregnancies.24 Patient fears and negative experiences surrounding CPCs, as well as a lack of knowledge about their anti-abortion mission of can foster confusion and mistrust in healthcare networks, even those beyond the field of obstetrics and gynecology.

CAUSAL LOOP DIAGRAM

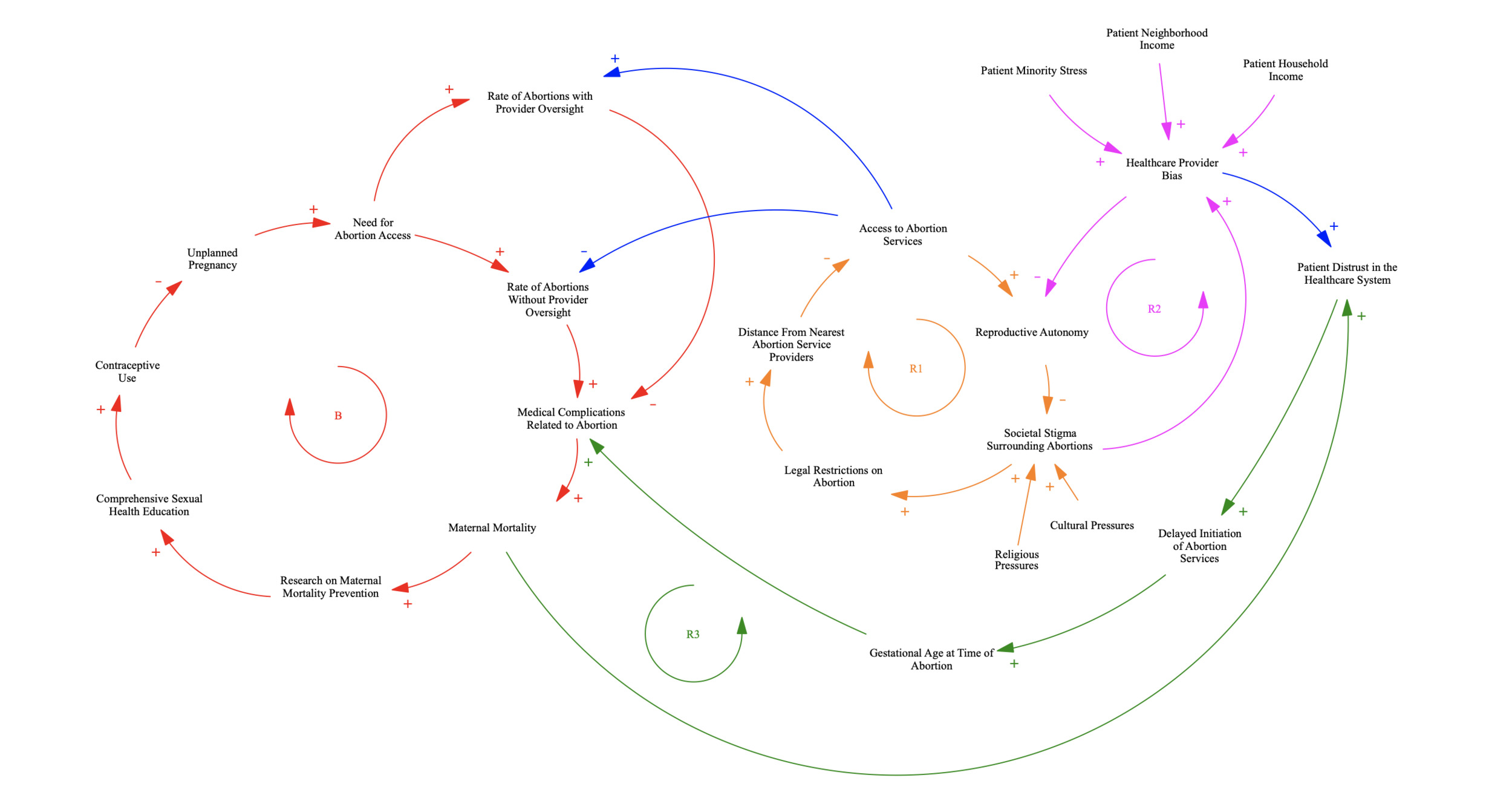

Using the NSRL findings, we developed a CLD containing four feedback loops summarizing the interconnections between abortion access and maternal mortality in the United States (Figure 1).

We identified a key balancing loop (B) highlighting comprehensive sexual health education as a critical intervention to reduce maternal mortality. We theorized that comprehensive sexual health education is positively associated with contraceptive use, and greater contraceptive use negatively contributes to unplanned pregnancies.25 However, when unplanned pregnancies do occur, the need for abortion services and the rate of abortions without provider oversight increases, demonstrating a positive causal relationship.26 These unsafe abortions, often those without direct medical supervision, are positively associated with medical complications, such as infection or hemorrhage, which heighten the likelihood of maternal mortality.10 Higher maternal mortality rates may lead to an increase in research on maternal mortality prevention, which in turn can expand access to comprehensive sexual health education.27,28 Comprehensive sexual health education offers a key opportunity to reduce unplanned pregnancies, unsafe abortions, abortion-related complications, and ultimately lower maternal mortality rates.

The primary reinforcing loop (R1) details correlations between societal stigma, legal restrictions, and access to abortion. We theorize that societal stigma is positively driven by cultural and religious pressures, which contribute to the implementation of legal restrictions like abortion bans.21 These legal restrictions increase the distance from the nearest abortion service providers, which is negatively associated with abortion access.29 However, as access to abortion increases, individuals have greater reproductive autonomy and control over their abortion care,30 reflecting a positive relationship. Ultimately, reproductive autonomy is negatively associated with societal stigma, reinforcing the proposal of broader access to abortion services.

The secondary reinforcing loop (R2) examines the correlations between healthcare provider bias, reproductive autonomy, and societal stigma, with a broader connection to abortion access (as shown in R1). We theorize that patient minority stress,17 alongside neighborhood and household income, positively contributes to healthcare provider bias.16 This bias affects the care offered to abortion-seeking patients, often involving a lack of empathy, which can foster patient distrust.19 Another direct result of healthcare provider bias is reduced patient reproductive autonomy,31 which is positively associated with societal stigma.32 This societal stigma towards abortion reinforces healthcare provider bias.19 As a result, we propose that reducing both societal stigma and provider bias can allow for greater reproductive autonomy and promote equitable access to abortion.

The final reinforcing loop (R3) highlights the role of patient distrust about abortion-related medical complications and maternal mortality. As discussed in R2, when patients experience the effects of care based on healthcare provider bias, it positively contributes to patient distrust in the healthcare system.19 We theorize that this distrust is positively associated with a delayed initiation of abortion services, which increases the gestational age at the time of abortion.12 Delay in care results in later-stage pregnancies, which limit abortion options and increase the risk of medical complications.12 Abortion-based medical complications positively contribute to rates of maternal mortality,12 which we theorize further intensifies patient distrust and creates a reinforcing cycle.

We also highlighted the broader connection between access to abortion services and the rates of abortions, both with and without provider oversight. Abortion with provider oversight refers to abortion care with direct involvement from a qualified healthcare provider, ensuring medical supervision throughout treatment. These direct connections demonstrate how greater accessibility to abortion services is positively associated with safer abortion care, while reduced accessibility correlates with an increase in unsafe abortion care.10

DISCUSSION

Proposed Interventions

Comprehensive Sexual Health Education

Comprehensive sexual health education goes beyond teaching abstinence by covering an expansive range of topics, including sexually transmitted infections (STIs), contraception (such as condoms, birth control pills, and other methods), sexual activity, pregnancy, and more. It provides accurate, age-appropriate information on sexual and reproductive health.33 National curriculum frameworks, such as the CDC’s Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool, guide educators in setting accessible learning objectives to promote sexual health awareness. Specifically, HECAT encourages students to evaluate the potential consequences of sexual behavior, such as the financial and social impacts of unintended pregnancy, with the hope that this provokes deeper reflection on the responsibilities of parenthood.34

Various studies demonstrate that comprehensive sexual health education programs are more productive than abstinence-only approaches in preventing the rate of unintended pregnancy by reducing sexual activity and increasing contraceptive use among sexually active youth.35 Implementing comprehensive sexual health curricula in schools can be particularly effective by amplifying awareness of sexual health at a time when many youth are exploring relationships for the first time.36

Globally, approximately 61% of unintended pregnancies are terminated, highlighting the need for better prevention strategies such as comprehensive sexual health education.26 Particularly in areas with restrictive policies, comprehensive sexual health education can be a tool in reducing unintended pregnancies, thereby helping to mitigate the need for abortion.

Reproductive Healthcare Provider Training & Support

Training and support for reproductive healthcare providers is key to improving abortion care access through addressing provider bias—a factor that both drives and results from abortion restrictions. Bias-reduction programs help providers identify and address biases, such as favoring childbirth, which may hinder patient autonomy. Effective strategies include facilitating open discussions among providers, using role-playing exercises to promote empathy, and adopting a non-punitive approach. These efforts can reduce stigma, build patient trust, and expand access to care, ultimately improving maternal health outcomes.18

Furthermore, standardized protocols for supporting reproductive healthcare providers—covering areas such as obstetric emergencies and patient counseling—are critical, particularly in “obstetric deserts” where abortion bans have severely limited care. Restrictive laws have also contributed to “hesitant medicine,” with providers relocating to protect their licenses and careers. Retaining healthcare providers through bolstering resources and recruitment in these underserved areas is essential for ensuring equitable access to care.15

Reducing bias among healthcare providers can significantly amplify reproductive autonomy, defined by the Center for Reproductive Rights as the right to decide if, when, and how to become pregnant and raise children. Studies report that non-judgmental care empowers patients to make informed reproductive health decisions, thereby facilitating autonomy.31

Beyond bias reduction, it is also critical to expand the abortion care network by training Advanced Practice Clinicians (APC), who are qualified non-physician providers such as nurse practitioners and midwives, particularly in underserved areas with restrictive abortion policies.37 At the policy level, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has called on legislators to eliminate mandates on physician-only abortion care provision, which creates unnecessary barriers to care. In 2022, only sixteen states allowed APCs to perform both medication and surgical abortions.38 Increasing the number of APCs authorized to prescribe medications for abortion can significantly benefit patients living in states with restrictive abortion bans as they now can seek care in neighboring states.

Studies have concluded no significant difference in complication rates by providers with different years of experience in medication abortion (RR = 1.00, 95% CI 0.97-1.04), and APC-provided medication abortion met established benchmarks for both safety and effectiveness when compared to physician-provided care.37,39 With the approval of Mifeprex (mifepristone) by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2020 as the first drug for medical termination of pregnancy, medication abortions have become increasingly common.40 In 2023, the Guttmacher Institution reported that medication abortion accounted for over 60% of all abortions in the formal US healthcare system.40,41

The rise of medication abortion and the demonstrated competency of APCs in providing care have prompted policymakers and health administrators to integrate APCs into the formal abortion care continuum. Therefore, healthcare institutions should prioritize hiring APCs while integrating comprehensive abortion training and standardized training protocols into the abortion education programs. Specifically, partnerships between physicians and APCs should prioritize structured mentorship and continuing education programs.42,43 These initiatives should aim to address the current gap in formal abortion training for APCs before they enter practice. Through these efforts, APCs can be fully integrated into the formal healthcare system as essential providers of medication abortion, which will not only expand patient access to abortion but also alleviate the burden on physicians.

Community Advocacy

Efforts to address the connection between abortion access and maternal mortality will become even more challenging due to an increase of conservative representatives and officials across the federal executive, legislative, and judicial branches.44,45 Many states that banned abortion post-Dobbs—like Louisiana, Alabama, and Texas—have relied on federal protections to safeguard reproductive rights, which has been particularly evident in the flow of federal funding to universities and community-based organizations.46 The federal government’s past support through grants from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and other federal agencies allowed these entities to provide critical reproductive health services and resources46–48 without fear of state-level funding cuts.

In the short time after the November 2024 general election, local efforts in states with restricted abortion access have faltered or fragmented, primarily due to shifting political rhetoric and policy proposals. Plans to reduce federal support for reproductive health services and increase regulatory oversight have further weakened local initiatives.47 At all levels of government—local, state, and federal—those working to protect or expand reproductive rights will have limited power to counter legislative and regulatory changes.44,49 The scale of the human lives affected by these policies is difficult to quantify fully, but they represent a significant shift in public health policy.

In response to a lack of governmental power, advocates for abortion rights will be forced to develop and implement interventions largely independent of public resources, relying instead on grassroots efforts and community-driven solutions. This approach will involve building coalitions, organizing at the local level, finding workarounds to restrictive laws, and supporting non-profits. Effective advocacy will require a realistic assessment of available tools and resources, focusing on what can be done within these constraints. In the years leading up to the 2026 election, the country is likely to experience further legal regressions, pushing many states back to conditions reminiscent of the pre-Roe era regarding reproductive rights.

Maternal Mortality Reporting

Grassroots-level community-driven solutions also extend to supporting non-governmental institutions to ensure consistent reporting of maternal mortality. Maternal mortality has long been used as a critical indicator of population health, and accurately measuring maternal mortality is the essential first step for any prevention program.50,51 However, the inconsistency of maternal mortality across different states has been a significant issue. Specifically, the scope of work, committee structure, report requirements, and/or the review process vary significantly among the 49 states with formal Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs).52 Despite states’ revisions in the last 15 years to incorporate the “Pregnancy Status Checkbox” in the Standard Certificate of Death, protracted time and inconsistent implementation have resulted in cross-sectional research gaps on maternal deaths.53

MMRCs are also subject to varying state policies that can significantly impact the rigor and depth of their investigations of maternal deaths. For example, the release of the 2019 maternal mortality report in Texas was delayed by over three months, which has been condemned as politically motivated and an act of “dishonorably burying these women.”54 For studies that rely on timely and accurate maternal death data, delayed release and inconsistencies in maternal death data may reduce the reliability of their statistical findings. Therefore, it is critical to foster community efforts and support non-governmental research agencies in collecting, reporting, and publishing accurate data on maternal mortality.

LIMITATIONS

Our literature review featured a limited representation of qualitative studies. Although we recognize the importance of in-depth analysis of qualitative studies, fewer than five of the 25 published sources we analyzed were primary analyses of original qualitative research. To ensure statistical validity in assessing the main correlational and/or causal relationships between significant variables in the CLD, we instead mainly focused on secondary analyses from scoping reviews, surveillance data, and other quantitative studies, which may inadvertently sideline the nuanced perspectives qualitative research provides (e.g., personal narratives, ethnographic research, and case studies). Reviewing qualitative studies—particularly studies examining motivations behind anti-abortion stances —is crucial to understanding the full scope of abortion care access. For example, anti-abortion discourse in legislative hearings is used to study the dissemination of unsubstantiated personal claims that contradict medical claims by anti-abortion healthcare providers.55 In the future, incorporating more qualitative studies can offer a multifaceted understanding of the barriers abortion care seekers face.

Another limitation of the CLD in this NSRL is the simplification of its feedback loops, which achieves clarity but lacks nuance by excluding minority experiences and intersectional factors of accessing abortion and resulting policy recommendations. For example, reducing healthcare provider bias on abortion care seekers might not fully address cultural or linguistic barriers faced by immigrant populations, nor would it eliminate medical distrust in communities with a history of healthcare exploitation. In the future, an important research focus might lie in detailing the unique intersectional pathways of accessing abortion care in different communities using CLDs. Only in this way can we develop targeted public health interventions for varying populations based on their distinct needs.

CONCLUSION

This review highlights the importance of considering multiple factors when addressing the relationship between abortion access and maternal mortality rates. In the current U.S. political climate, especially in the wake of a turbulent election season, the topic of abortion has become a highly debated and controversial topic. It is likely that with shifts in federal and state leadership, abortion access will be increasingly restricted. Consequently, women in the United States will experience decreased bodily autonomy, leading to worsened maternal health outcomes, as demonstrated by numerous studies, including this one. Key factors highlighted in this review—including access to comprehensive sexual health education, legal restrictions on abortion, healthcare provider bias, and patient distrust in the healthcare system —will be essential focuses in the fight for abortion access.

In light of the discussions of abortion access and maternal mortality in this review, abortion rights advocates must develop and implement data collection strategies and interventions largely independent of government resources. Instead, we should rely on grassroots efforts and community-driven solutions, especially given the significant variations in reporting standards influenced by politics. At the same time, it is crucial to remain empathetic and remember that statistics are not solely numbers, but they are real women with real-life experiences. As a nation, we must work toward ensuring safe abortion access to protect the health and well-being of all women in the United States.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Johns Hopkins University Public Health Studies Program.

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

About the Author(s)

Amber Yu

Amber Yu is a third-year undergraduate student at Johns Hopkins University double-majoring in Molecular and Cellular Biology and Public Health Studies. Her research areas include breast cancer disparities and surgical education.

Annie Pan

Annie Pan is an undergraduate student at Johns Hopkins University double-majoring in Public Health Studies and Applied Mathematics and Statistics. Her research areas include public health, spinal cord injuries, and mental health.

Gurkamal Kaur

Gurkamal Kaur is an undergraduate student at Johns Hopkins University double-majoring in Molecular and Cellular Biology and Public Health Studies. Her research areas include familial pancreatic cancer and maternal and reproductive health.

Isabelle Jouve

Isabelle Jouve is an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins University majoring in Public Health Studies. Her research areas include sexual and reproductive health.

Yue Yu

Yue Yu is a third-year undergraduate student at Johns Hopkins University double-majoring in Public Health Studies and Applied Mathematics & Statistics. Her research focuses on studying infectious disease through mathematical modeling.

Tom Carpino

Tom Carpino is a Gordis Faculty Teaching Fellow at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health. His primary research interests include social and behavioral epidemiology.