Introduction

Violence against marginalized populations, including women, minors, and members of the LGBTQIA+ community, is widespread across the globe. One in three women will experience physical or sexual violence by either an intimate or non-intimate partner in their lifetime.1 Additionally, approximately one billion children worldwide face some form of physical, sexual, or psychological abuse each year.1,2 As of 2025, 64 countries still outlaw same-sex attraction, and LGBTQIA+ individuals face increasing discrimination worldwide.3 Perhaps most troubling, 78.8% of global murders of transgender people occur in South America, where the average life expectancy for a transgender individual is just 35 years, compared to 72 years for the general population.4,5

In Brazil, the prevalence of gender-based violence (GBV) and intimate partner violence (IPV) among marginalized populations is equally as alarming. As of 2019, approximately 16.7% of Brazilian women between the ages of 15 and 49 years reported being subjected to physical or sexual IPV at least one point in their lifetimes.6 IPV can be a component in the continuous patterns of abuse experienced by Brazilian women; 33% of female IPV victims in Brazil report recurrence of violence.6 Femicides, or the intentional killing of a woman due to her gender, is prevalent in Brazil with approximately one woman dying every seven hours.7

Similarly, Brazilian children and adolescents are at risk for experiencing both physical and sexual violence. Approximately 73.3% of reported cases of child sexual abuse in Brazil occur against girls ranging from 6 to 10 years of age.8 According to data retrieved from the 2015 Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar (PeNSE) data set, Antunes et al (2020) found that 10% of Brazilian adolescents reported having experienced physical violence at the hands of a relative while 70% of those victims experienced multiple instances of physical violence in the month prior.9 In a cross-sectional study conducted by Hildebrand et al (2019) in the state of Sao Paulo, it was found that 1 in 4 Brazilian children are subjected to physical violence while 1 in 5 Brazilian girls has experienced sexual abuse.10 As of 2019, Brazil is ranked fourth among countries with the highest incidence rate for child murder.10

Discrimination against members of the LGBTQIA+ community is prevalent in Brazilian society as well. Of the 12,477 criminal complaints filed in Brazil from 2011 to 2017, approximately 22,899 violations were found to be committed against members of the LGBTQIA+ community.11 In a study conducted by Ferriera et al (2022) examining the prevalence of violence and discrimination against Brazilian men who have sex with men, it was found that 23.5% of respondents reported experiencing physical violence due to their sexual orientation and that 66.9% of respondents suffered various forms of discrimination due to their sexual orientation.12 Rufino et al (2021) found that lesbian and bisexual women are similarly subjected to physical violence and experienced a 150% increase in murder related to “hatred, revulsion, and discrimination” between 2014 and 2017.13 Transgender individuals are twice as likely than their cisgender counterparts to be assaulted and have a 90% to 100% chance of experiencing traumatic events over the life course.4

A variety of factors come into play regarding violence against marginalized populations in Brazil. Overall, females, female presenting individuals, children, and black or indigenous individuals are most at risk for experiencing physical or sexual violence in Brazil.14,15 More specifically, women are most at risk of dying from physical and sexual violence at the hands of an intimate partner if they are Black or brown, disabled, are residing in a rural area, or if their partner is under the influence of drugs or alcohol.11,15 Additionally, De Vasconcelos et al (2021) found that women who were unable to complete a high school education are believed to be at a 40% increased risk of experiencing IPV in adulthood.6 Most violence perpetuated against minors occurs in the victims’ domicile and the perpetrator is often related to the victim (parents, sibling, extended family member) and inebriated.8

Violence is heavily associated with male perpetrators and the lack of safe and caring environment and connection to paternal figures increases the overall risk of future traumatic events.16,17 Furthermore, these occurrences of violence uphold patriarchal societal norms that contribute to current gender roles and inequalities being sustained, further exacerbating gender-based violence for future generations in Brazil.18

Factors affecting violence within the LGBTQIA+ community differ by subgroup. Brazilian men who have sex with men are more at risk for experiencing violence if they are black or brown, live near or with their aggressor, have a lower educational status, and if they receive money in exchange for sex.19 Transgender, lesbian, and bisexual women are the most at risk LGBTQIA+ groups to experience violence because they are women.4,13 Transgender women have “fragile” support networks that present difficulties if they were to leave their aggressor or report criminal violations.4 Additionally, social exclusion increases negative socioeconomical determinants such as poverty, racism, and subpar educational status increasing the rates at which they experience physical and sexual violence.4

In total, gender-based violence and interpersonal violence are responsible for the loss of approximately 175,000 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in Brazil over the last two decades.6 These occurrences of physical, sexual, and psychological violence within marginalized populations play a key role in the development of long-term health complications, in addition to oppressive and discriminatory policies and societal norms.19 As of 2019, Brazilian women aged 18-49 lost approximately 80,000 potential years of life (YLL) due to physical and sexual violence prevalent in Brazil.6 Women often experience a myriad of health effects due to GBV and IPV; physical trauma, unwanted pregnancy, miscarriage, substance use disorders, infectious diseases, maxillofacial injuries, and death.7,20,21

For Brazilian children and adolescents, childhood sexual and physical abuse can lead to subpar educational performance, increased risk of developing psychiatric disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, and an increased risk of dying by suicide.8,10 Furthermore, abuse against adolescents presents the possibility of developing long term health effects such as increased risk of sexually transmitted infections, pregnancy, eating disorders, sleep disorders, and serious mental health complications.22 Minors who have experienced some type of abuse or violence are at a higher risk of future revictimization.16

Violence against members of the Brazilian LGBTQIA+ community often have lethal consequences.23 LGBTQIA+ individuals experience transgressions such as physical abuse, public attacks, sexual aggression, corrective rape, torture, and murder.23 Violence can influence the extensive discrimination experienced by LGBTQIA+ individuals within formal institutions such as the healthcare system, educational institutions, or the workplace, leading to adverse physical and mental health effects.13

While it is recognized that GBV and IPV are becoming increasingly prevalent and deadly within Brazil, there are limited resources or structure available to provide assistance and justice for victims. Victims are often too afraid to come forward and name their aggressor in fear of the social repercussions from their social support circle or aggressor retaliation.6

Currently, there are few recent studies identifying and evaluating interventions targeting women, minors, and the LGBTQIA+ community in Brazil. Most currently published studies focus on groups such as women and children, providing little to no data on LGBTQIA+ populations. Additionally, most studies were published before the COVID-19 pandemic, offering no updated information on interventions in a post-pandemic context. The purpose of this scoping review is to provide a map of the most current literature published surrounding current strategies and interventions being utilized to address gender-based violence in Brazil.

Methods

Search Strategy

A search of publications evaluating the effectiveness and feasibility of domestic and interpersonal violence prevention interventions in Brazil was conducted between June 2023 to February 2025. Embase, EBSCO, PubMed, and Google Scholar were used due to their high reliability and concentration of potentially relevant publications. Publications reviewed were limited to empirical studies published in peer-reviewed journals between the years 2019 and 2023 with no restrictions on the language of publication.

Article screening was conducted using Covidence, with a single screening approach applied to both title/abstract and full-text reviews.24 Search terms included “gender-based violence,” “domestic violence,” “violence,” “femicide,” “abuse,” “LGBT,” “interventions,” “strategies,” “Brazil,” and “Brasil.”

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in this scoping review, selected empirical studies were required to target or have a direct impact on populations of interest, such as women, children, or LGBTQIA+ individuals specifically within Brazil. Additionally, publications were included if the outcomes presented were participant generated, such as data collected from interviews, surveys, or a set of participant recommendations. Publications were excluded if they were categorized as reviews, commentaries, or conference papers.

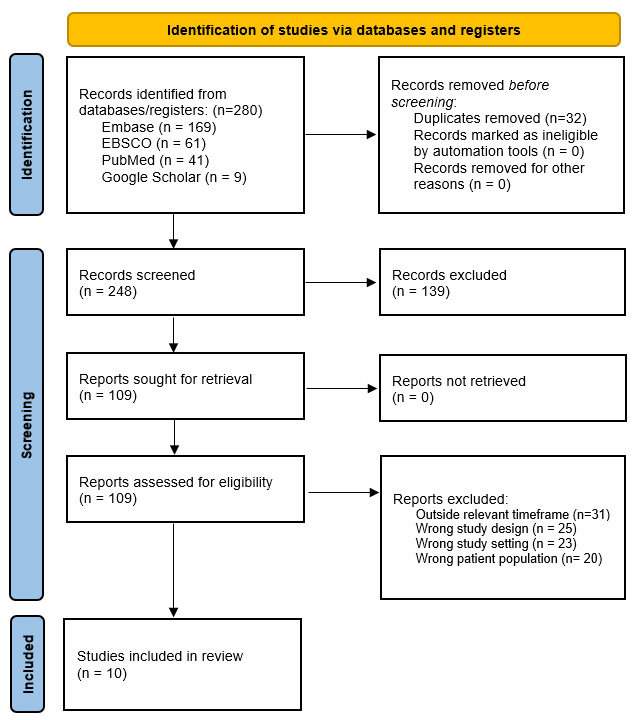

The initial database search resulted in 280 publications across all four databases. PubMed produced 41 results, Embase produced 169 results, EBSCO produced 61 results, and Google Scholar produced 9 results. A total of 32 duplicate results were removed before screening. Next, 248 titles and abstracts were screened for relevancy; 139 publications were excluded. The last 109 publications were assessed for eligibility, and a total of 99 were excluded for the following reasons: outside relevant time frame of publication (n=31), wrong study design (n=25), wrong study setting (n=23), and wrong patient population (n=20). The remaining ten articles were selected to be included in this scoping review. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram depicting the identification and selection process of included publications can be found in Figure 1.

Results

Publication Characteristics

All publications included in this scoping review were published in Brazil. Most articles were published in English, while three articles were published in Brazilian Portuguese. However, English translations of these three articles were available for review. Articles were published between the years 2019 to 2023 with the highest concentrations being 2021 and 2022 (n=3, respectively). About five articles were sourced from Embase, three from PubMed, and two from EBSCO. Of the study areas of research, five articles were published in the public health field, one in the medical field, two in nursing, one in legal, and one in psychology.

In four reported studies, researchers examined the effectiveness and/or feasibility of interventions designed to address and limit gender-based violence and interpersonal violence in their selected populations.25–28 The remaining six articles focused primarily on the development and implementation of interventions designed to address gender-based violence in their selected populations.29–34 These interventions addressed violence at all levels of prevention: primary (n=5), secondary (n=2), and tertiary (n=4). One intervention presented components that addressed both primary and secondary prevention measures. A table depicting selected publication characteristics can be found in Table 1.

The publications included in this scoping review varied across settings and modes of delivery. Most interventions selected were conducted online (n=4), in a community (n=3), healthcare (n= 2), or emergency housing setting (n=1).

The four online interventions and studies; conducted by Murta et al. (2020), Baptista et al. (2022), Signorelli et al. (2023), and Silva et al (2021); primarily focused on primary and secondary prevention and self-efficacy building. Murta et al. (2020) examined the effectiveness of an intervention designed to address dating violence in adolescents through a comprehensive online educational program. Participants completed four online sessions including information regarding conflict management, risk perception of violence, self-efficacy, and building social support.32

Baptista Silva et al. (2022) examined the development and effectiveness of an online health platform, the Dandarah App, designed to inform members of the Brazilian LGBTQIA+ community of potential discriminatory areas in their community as well as safe spaces for queer individuals. Results from this study provided evidence that the Dandarah App was user-friendly and had the potential to provide the needed safety assistance to the Brazilian LGBTQIA+ community.29

Signorelli et al. (2023) detailed the implementation of an online safety decision aid for Brazilian women experiencing domestic and gender-based violence. This online intervention effectively assisted program participants in “establishing safety priorities” and safety plans to effectively leave an abusive situation or relationship.27

Silva et al. (2021) examined an online terminology application designed for medical personnel addressing violence and abuse against children, creating a consolidated and effective approach to registering and monitoring potential abuse cases. It was found through this examination that this terminology application was feasible in providing nurses with the effective and appropriate means in reporting violence against children.34

Three studies included the evaluation or examination of community-level interventions primarily focused on health education and crime prevention.25,26,31 Murray et al. (2019) detailed an effective intervention, the Pelotas Trial of Parenting Interventions for Aggression (PIA) trial, used to prevent violence against children through early life health education of parents and their children. This intervention was developed to address “harsh parenting” and “poor cognitive development” through low-cost parenting interventions and was found to have the potential to be effective in reducing child abuse.26

Dixe et al. (2019) utilized community forum theatre to educate minors of the potential harm and risk-factors of violence in intimate partnerships. In this intervention study, the researchers found that community engagement and education allowed adolescents the opportunity to talk about their experiences and access assistance more effectively.25

Macauley (2021) examined the Maria da Penha program, a community-based intervention that involved second-response police patrols strategically designed to provide support and care to repeat victims of domestic violence. Women who received support through the Maria da Penha program were at a lower risk of experiencing repeated assaults or consequent femicide compared to women not enrolled in the program.31

Foschiera et al. (2022) and de Jesus et al. (2021) both conducted studies of healthcare interventions primarily focused on tertiary prevention and the effectiveness of medical personnel in follow-up care. Both interventions examined involved providing care to women after one or multiple documented assaults. In the intervention developed by Foschiera et al (2022), female participants were provided with cognitive behavioral therapy after sexual assault and violence. Results showed that providing victims with adequate mental health care, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, reduced rates of subsequent depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and complex trauma.28

De Jesus et al (2021) examined the assistance provided by healthcare providers to female victims and follow-up referral intervention. They found that female victims who were effectively referred to healthcare assistance within the 72 hours after a sexual assault improved a woman’s recovery process and overall sexual health.33

Evans et al. (2021) assessed a femicide risk assessment tool, the Danger Assessment-Brazil, developed for use at emergency housing shelters for women. Program participants completed a data collection survey and cognitive interview to detail their experiences and home environment details.30 Data collected from this intervention provided substantial information regarding the feasibility of a nationwide risk assessment tool as well as providing women more effective and informed care.30

These publications presented common themes and modes of intervention delivery. Publications focused on either health education of potential/current victims of violence/potential perpetrators of violence or increasing access to invaluable services or resources for survivors of violence or potential victims of violence. Self-efficacy building in targeted populations (women, minors, and LGBTQIA+ individuals) was a common theme as well, despite not being specifically identified in several publications. Additionally, most studies utilized primary or tertiary prevention techniques in their interventions. Studies examining the effectiveness or delivery of care in female populations utilized tertiary prevention techniques while those examining interventions targeted towards minors solely utilized primary prevention techniques.

The selected publications differed in their study design, sample size, and study settings. While some studies varied between utilizing randomized control trial and cohort study designs, most of the selected studies employed other studies designs such as Community-Based Participatory Research, pretest-posttest quasi experimental study design, and triangulation approach. The sample sizes of the selected publications varied between 3 and 1,220, with a median value of 248.5. Finally, study settings differed between selected publications with most studies taking place online, followed by community-level interventions, healthcare interventions, and emergency shelter interventions. These study settings provide participants with differing types and levels of care and differing parameters for researchers to gauge effectiveness and feasibility.

Discussion

This scoping review provided insight into the GBV and IPV prevention capacity of Brazil, the methods used to address violence, providers most often utilized, and implementation settings. A total of 10 publications fit the parameters of this study and were used to create an updated, post-COVID map of the most current literature regarding GBV and IPV interventions in Brazil.

Interventions were mapped according to the target population of interest. Much of the interventions retrieved were targeted towards women (n=5) and minors (n=4). There was an immense gap in services provided solely to those of the LGBTQ community; only one publication retrieved focused on preventing violence against queer individuals. This result mirrors what was discussed by Pinto et al; societal apprehension and discrimination against Brazilian queer individuals limits the attention paid to violence committed against that population.23

Interventions retrieved were consistently used to address the primary (n=5) or tertiary (n=4) levels of prevention in the respective population of choice. One intervention was used to address solely the secondary level of prevention while another intervention focused on both primary and secondary prevention techniques. All primary prevention-based interventions targeted prevention of violence and abuse against minors, while all tertiary prevention- based interventions targeted women. This finding may be due to the differing types of violence or abuse as well as the perpetrators of said violence. Additionally, gender-based violence against women has been normalized in Brazil, leading to a possibility that this difference may be due to violence against women not always perceived as a reportable offense.6

In childhood violence prevention interventions and programs, resources and education are targeted towards the parents and families of at-risk children. Individuals related to or otherwise close to children and adolescents are more likely to be perpetrators of abuse.9 This reality presents an opportunity for public health professionals to address violence at the source before abuse can occur using primary prevention techniques and interventions.

The types of interventions implemented differed across all three target populations, primarily in the mode of delivery. Interventions targeted children and their immediate support system were conducted in educational settings like elementary schools, daycares or online. Parents and their children were engaged through community-based practices that involved education on the risk factors and outcomes of childhood abuse and an opportunity to share their experiences with other community members that could be trusted. Online interventions were crucial in educating families and healthcare professionals of the warning signs of child abuse and building self-efficacy.

Interventions that targeted women and queer individuals utilized online-based, hospital-based, and community-based settings. These settings all influenced the outcome and effectiveness of each intervention. Online interventions were consistently used throughout most interventions and were effective. However, the lack of face-to-face contact and rapport with a community health worker may have affected the long-term outcomes of these interventions. Many participants across interventions retrieved noted the importance of connecting with another individual in-person to discuss the events that they have experienced. This contact with another trusted person outside of the abusive relationship or situation allowed victims to speak candidly and work to build self-efficacy. Nonetheless, online-based interventions provide much needed education and access to a wide range of people with diverse backgrounds. With online educational interventions, participants were effectively given the full range of information available for them to either recognize when a relationship is turning abusive or to develop the self-efficacy and resources needed to leave an abusive situation. Additionally, online-based interventions provided queer individuals with the information required to make effective safety decisions when outside of their homes or other safe places.

There were consistencies among the interventions retrieved. Online-based interventions were utilized in all three populations. These online interventions provided target audiences with equitable access to information and care compared to other intervention types. Additionally, many interventions utilized participant feedback in the development and implementation of programs. Community-based and hospital interventions utilized connection and rapport building with participants, allowing for deeper conversations regarding abuse and potential solutions for demanding situations.

This study mapped the current extent and range of published literature regarding GBV and IPV interventions in post-COVID Brazil. Additionally, this study determined the immense gaps of service for all three outlined populations of interest, but specifically the gaps in service and research for women and queer individuals. These gaps include lack of primary prevention resources and lack of community-based and public health advocacy. For the LGBTQIA+ community, the lack of interventions aside from imminent and real-time safety resources may add to the burden of violence experienced by this community.

Limitations

The limitations of this study presented challenges in providing the full breadth of GBV and IPV prevention in Brazil. Namely, unpublished information regarding GBV and IPV interventions in Brazil could not be retrieved or analyzed. This includes community-based interventions with no published data and government-level interventions with little to no published data. Additionally, no risk of bias assessment was conducted of the reviewed and included publications of interest. However, this study provided much needed insight into the current GBV and IPV prevention landscape of Brazil in a post-COVID world. To our knowledge, there are no current, post-COVID scoping reviews examining the prevalence, efficacy, and feasibility of GBV/IPV interventions in Brazil.

Recommendations

No country is completely free of violence against marginalized populations, including Brazil. Future research and evidence-based interventions need to be conducted and implemented to address the specific needs of the Brazilian LGBTQIA+ community. Although there are differing viewpoints regarding queer rights in Brazil, the reality is that LGBTQIA+ community members bear much of the violence burden compared to their straight and cis counterparts. Similarly, interventions in the future must implement primary prevention techniques for both women and LGBTQIA+ community members.

Interventions in the future should approach GBV and IPV through a holistic lens, providing essential educational material while also addressing the mental and emotional state of the victim. Of course, organizations vary in their capacity to provide such thorough assistance, but looking at the experiences of survivors as multifaceted can yield effective and sustainable results. Additionally, policymakers should consider strengthening legal protections for survivors, expanding funding for survivor support services, and integrating gender-inclusive violence prevention strategies into national public health initiatives.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the most effective interventions were those that were deeply involved with the personal development of program participants and provided substantial education in addition to counseling and discussion. These interventions often viewed participants holistically and recognized the political and social landscape of Brazil regarding GBV and IPV.

This scoping review is significant in that there are currently no current, post-COVID scoping reviews examining the prevalence of GBV interventions in Brazil targeting women, minors, and queer individuals.